Games are always about conflict. It’s not always conflict with other players, but there’s always some objective function to be optimized against some set of constraints. Often, that conflict involves control of something; resources, land, people, opinion, communication, whatever. These objectives are often multi-part and various parts have varying relationships with other parts. This is most obvious with land; a given plot of land borders some areas but not others. This shared conflict space and its internal relationships must be represented on the board somehow.

Thanks to Clint Davey, an excellent board game design analyst, and Morgane Gouyon-Rety, designer of the wonderful Pendragon for the inspiration!

Designers might consider how to represent adjacency on their boards for a lot of reasons, and it’s almost always one of two ways, Area and Point to Point. It seems a common belief that it doesn’t matter, anything you can do with Area representation, you can do with the other, it’s just a matter of which is better for your game.

In this article, I’ll show that Area and Point to Point are not equivalent and that there are adjacency representations possible in Point to Point representation that are not possible in Area representation. Further, I’ll show you how to tell if the adjacency you’re trying to represent is one of those cases that requires P2P.

First, though, let’s look at these two approaches, why they’re popular, and what each is good at from a design perspective. Feel free to skip to the Analysis section if you’re confident you won’t find anything new here.

We’ll just look at maps representing physical territory, since that’s the most common and most obvious. Which areas are accessible by which areas is perhaps the most crucial assessment to be made from a given map in a conflict simulation.

The representation in Risk, where areas are represented by literal areas and movement happens across borders, is often called “area” or “area control” and is the most natural representation of adjacency and proximity because that’s how we make maps to use in real life. It requires the least mental translation to match with our intuition about how terrain works.

But an Area representation comes with inherent drawbacks. The physical size of an area doesn’t necessarily align with its value and the mismatch can be jarring and lead to unintentionally poor play (which might be the design goal of the game). Adjacency is also automatic, whether it makes sense or not, and exceptions must be made explicitly.

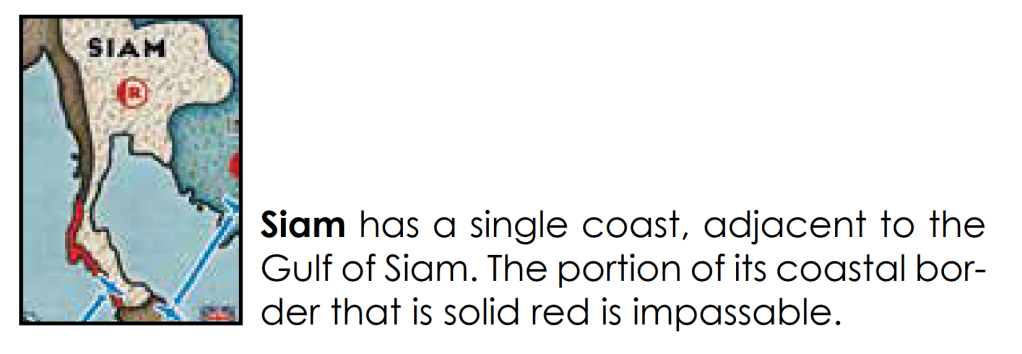

In the above representation the flawed work of genius that is Cataclysm: A Second World War, we see two examples. The bright red border means that the sections of the map sharing that border that appear adjacent are not. We also see instances of blue lines connecting two non-adjacent areas; this tells us that these sections that are not adjacent can be treated as adjacent by aircraft.

The second major approach to representing adjacency is often called “point to point” because it abstracts areas down to ambiguously-sized points with adjacency represented by explicit connections.

We already see some hints as to why we might prefer P2P over Area (and some reasons why we might not).

In the middle of Italy, Siena and Ancona are not adjacent; troops cannot march from one to the other. They are separated by mountains, but this isn’t necessary to express on the map since the absence of a connection is implication enough. In an Area representation, we’d need a Cataclysm-style colored border to indicate non-adjacency. In the other direction, we see the famous Straits of Messina and how one side connects to the other; the logistics of transit through and around this Strait have been tactically and operationally relevant in more than one instance in history, and this is difficult to express with Area representation.

The cons of P2P are immediately obvious; while it’s clean and elegant to express exceptions to adjacency, all adjacency must be shown explicitly, leading to a lot of map clutter. Compare the above Here I Stand with the clean, obvious borders of Cataclysm:

You barely even notice the borders in Cataclysm because borders are expected; their meaning comes front-loaded and do not need to be explained.

P2P is often most advantageous when geography alone isn’t enough to express adjacency.

Twilight Struggle, unlike many wargames, isn’t about bombs and bullets, but about hearts and minds. Belief, alignment, policy, culture, and economy are more important than physical area (although that’s still relevant, of course); the map shows political adjacency, not solely physical adjacency. As a result, relying on physical borders presents an inaccurate representation of “closeness” or adjacency. We can see that Turkey, while adjacent to the USSR in geography is not adjacent to it politically. Similarly, Italy is not adjacent to Spain/Portugal geographically, but it is politically. You can find several other geography/politics mismatches here. The rulebook even specifically calls out this difference of representation:

Critically, notice how the connection between France and Algeria crosses the connection between Spain/Portugal and Italy. Ditto with Lebanon-Jordan and Israel-Syria. More on that in a moment.

Veteran board game players and designers are aware of these tradeoffs, and they’re always intelligently-made. The trouble comes from thinking that the decision is strictly design.

Analysis

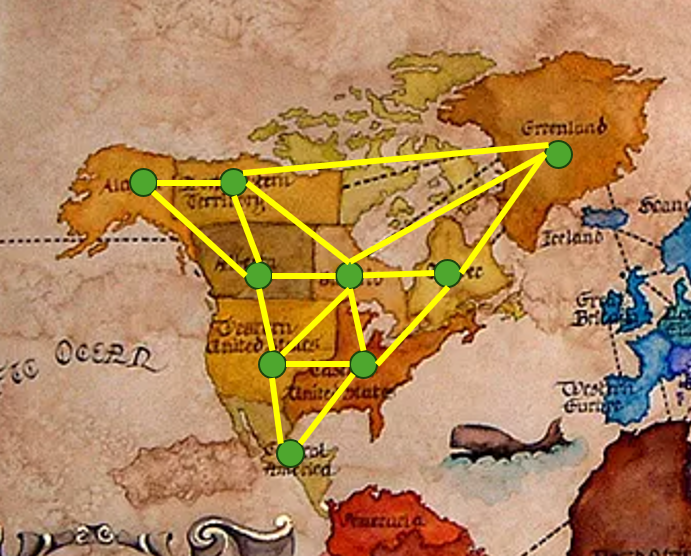

We can start to consider the equivalence of Area and P2P by looking at how to convert one to the other. Converting Area to P2P is straightforward: assign every Area Point and assign every border an Edge connecting the points of the Areas sharing the border. See how we’d do this using the Risk map from before, looking just at North America:

You might think that converting in the opposite direction is the same, but in reverse, but there is one critical limitation Area has that P2P does not: Edges in P2P can cross.

An Edge in P2P represents a border between exactly two Areas. It’s that exactly bit that’s the trouble. In 2 dimensions (where board game boards exist), it’s impossible for a border to be shared by more than two Areas and it’s impossible for a border to cross through an Area (if it did, it would simply make another Area and the border would again sit between exactly two Areas).

The math we’re going to look at is the very basics of graph theory. In math and computer science, a graph is a data structure represented by nodes (what we’re calling Points) and edges that connect them. Usually, board game borders can be crossed in either direction and they are shared between exactly two Areas, which means each border corresponds to an unweighted, undirected edge between two nodes. If a graph consisting of these edges and nodes can be expressed such that no edges cross, it is called a planar graph. So really, all we have to do is convert an Area map to a Point to Point map, then compute whether it’s planar. Luckily, this is easy; we don’t even need an algorithm.

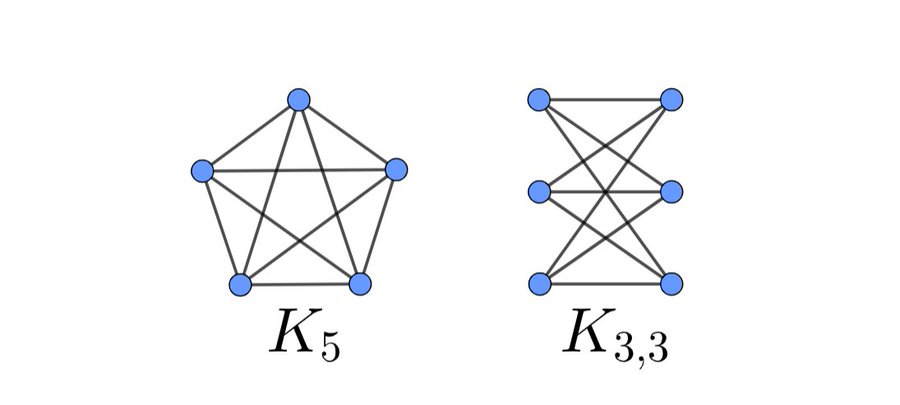

Wagner’s Theorem states that a graph is planar if and only if it does not contain two specific graph structures, K5 and K3,3 (or an equivalent graph), as a subgraph. If your P2P map contains either of these structures, it can’t be represented as an Area map:

K5 is relevant because it is a densely-connected graph; every node is adjacent to every other node. If your map has five or more nodes that are densely connected, it can’t be represented as an Area map.

Similarly, K3,3 is a graph of 2 groups of 3 nodes each, each of which is connected to each node in the other group. If your map has this substructure, it can’t be represented as an Area map.

This also applies to any supergraphs (adding more nodes doesn’t make these structures any more planar) and any subdivided graphs (splitting any of the edges by sticking a node in the middle of it doesn’t make it any more planar).

To intuit why this is so, let’s look at how we might try to represent K3,3 as an area:

D, A, F, and E are pretty easy to do. B looks a little different, but it’s possible. The trouble comes when we try to represent C. It has the same adjacency requirements as B, but B is already exclusively occupying the only space on the board that satisfies those adjacencies.

It’s easy to see that if we expand to 3 dimensions, this difficult goes away; you can just take B, tilt it out of the board, and you’re done. If you’re willing to get creative with the shapes of the Areas, in 3 dimensions, you can represent any P2P structure as an Area. Stuck in 2 dimensions, though, there’s nothing we can do.

The proof of Wagner’s Theorem is pretty simple on its own, but it requires understanding a lot of other pretty simple concepts about graphs first, like most graph theory. Graph theory is a bizarre field composed of a patchwork of lots of simple ideas, but it comes up basically all the time, so it’s a fun way to get into math as a hobbyist if you’re interested in that.

Conclusion

It feels unlikely but possible that a designer might stumble into a Kuratowski subgraph in their map design, so it’s good to know the theoretical limits of Area and P2P as well as the design tradeoffs of each.

Check out Clint Davey’s One Hour WWII, still in design: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1456271622/one-hour-world-war-ii

And seriously, please play Pendragon. Pendragon remains the only board game I’ve played where you physically bring the glittering loot from your raid back to your boats while the enemy chases you down and it is very satisfying. It’s like Escape From Tarkov for history nerds.